Open Innovation

In the fast-moving photonics industry, new product design and development is crucial for the survival of a company. Companies must continually improve the features, benefits, and performance of their products because of continuous advances in technology, competition, and the changing preferences and needs of customers.

Funding a new R&D project can be a real challenge in today’s economic climate. High-profile, capital-intensive R&D projects are investments to expand long-term possibilities but often have to be sacrificed in order to save jobs and workplaces here and now.

Yet, R&D is essential for new product development and can make the difference between a business moving ahead and losing the race.

In the past, R&D was a valuable strategic asset, especially when used as a formidable barrier to entry by competitors. Only large corporations like IBM, DuPont, Xerox, or AT&T Bell Labs could compete by doing the most R&D in their respective industries (and subsequently reaping most of the profits). Rivals who sought to unseat those powerhouses had to ante up considerable resources to create their own labs if they were to have any chance of succeeding via technological advancement.

These days, however, the leading industrial enterprises of the past are encountering remarkably strong competition from many upstarts. Surprisingly, these newcomers conduct little or no basic research on their own. Instead, they get new ideas to market through a different process.

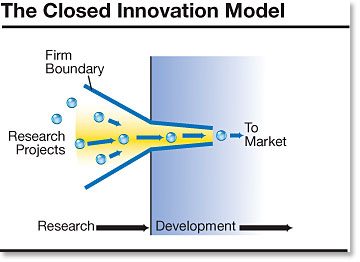

New business development processes and the marketing of new products have traditionally taken place within the firm boundaries of a company’s linear product-development funnel (Figure 1). Under this closed model of innovation, research projects are launched from the science and technology base of the firm. They progress through the development process, and some projects are stopped while others are selected for further work and advancement. Management and staff are essentially the sole source of new possibilities.

Several factors have led to the erosion of closed innovation and the philosophy of self-reliance in R&D operations. First, the mobility and accessibility of highly educated people has increased over the past 20 years. As a result, large amounts of knowledge now exist outside the research labs of large companies. Also, when employees change jobs, they take their knowledge with them, resulting in knowledge flows among firms.

Second, up until just a few years ago, the availability of angel funding and venture capital increased significantly, making it possible for promising ideas and technologies to be developed outside the traditional boundaries of the firm, typically in the form of entrepreneurial startup companies. Today, spinoffs, external licensing agreements, and cooperative agreements with suppliers are playing an increasingly important role in the innovation process.

Consider Lucent Technologies, which inherited the lion’s share of Bell Labs after the breakup of AT&T. Bell Labs was perhaps the premier industrial research organization of the last century, and this should have been a decisive strategic weapon for Lucent in the telecommunications equipment market.

However, things didn’t quite work out that way. Cisco Systems, which lacks anything resembling the deep, internal R&D capabilities of Bell Labs, somehow has consistently managed to stay abreast of Lucent, even occasionally beating the company to market.

What happened?

Although Lucent and Cisco competed directly in the same industry, the two companies were not innovating in the same manner. Lucent devoted enormous resources to exploring the world of new materials and state-of-the-art components and systems, seeking fundamental discoveries that could fuel future generations of products and services. Cisco, on the other hand, deployed a different strategy for innovation leadership. Whatever technology, ideas, and intellectual property (IP) Cisco needed, it acquired from the outside, usually by partnering or investing in promising startups (some, ironically, founded by ex-Lucent veterans).

By going outside, Cisco kept up with the R&D output of perhaps the world’s finest industrial R&D organization, all without conducting much research of its own.

The story of Lucent and Cisco is hardly an isolated instance. IBM’s research prowess in computing provided little protection against Intel and Microsoft in the personal computer hardware and software businesses. Similarly, Motorola, Siemens and other industrial titans with large research labs watched helplessly as Nokia catapulted itself to the forefront of wireless telephony in just 20 years. Nokia built on its industrial experience from earlier decades in the low-tech industries of wood pulp and rubber boots, only to be later eclipsed by companies like Apple, RIM and HTC.

Today, open innovation has become the new paradigm for organizing an externally-looking innovation process. Open innovation can be defined as the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and expand the markets for external use of innovation, respectively.

Open innovation assumes that companies can and should use external as well as internal ideas and paths to market as they look to advance their innovations and create value. Open innovation business models then define internal mechanisms to claim at least a portion of that value.

There are two important kinds of open innovation:

- Outside-in open innovation

- Inside-out open innovation

Outside-in open innovation involves opening up a company’s own innovation processes to many kinds of external inputs and contributions. It is this aspect of open innovation that has received the greatest attention, both in the literature and in industry implementation.

By transforming the meaning of “not-invented-here” inside your photonics company into an outside-in open-innovation development model, you can find new growth opportunities and bring hundreds of researchers from around the world on board to supplement your R&D activities. Likewise, researchers interested in partnering with a company that embraces the power of open innovation have incredible opportunities to change the world and get their science and technology “art” commercialized.

With knowledge now widely distributed, companies should acquire inventions or IP from other companies when it advances their business model. With huge investments in photonics R&D around the world, our industry is ideally positioned to leverage the open innovation model to harvest an exceptional variety of quality product and technology-development opportunities.

The lesser-known and practiced open-innovation model, inside-out, describes how organizations can allow unused and under-utilized ideas to go outside the organization for others to use in their businesses and markets. This can mean licensing unused patents and other IP to external users or creating a space within the organizations to nurture innovation and even encourage spinoff ventures under a different business model.

In an open innovation model, as depicted in Figure 2 below, a company commercializes both its own ideas as well as innovations from other sources, leveraging its traditional market pathways but also seeking new ways to bring these ideas to market via new, external company pathways.

Note that the boundary between the company and its surrounding environment is now porous (like a colander), enabling innovations to move more easily between the two. In many industries, and especially in photonics, the logic that supports an internally oriented, centralized approach to R&D has become obsolete. Useful knowledge has simply become too widespread and ideas must be shared and harvested.

Future innovative companies will successfully convert from Not Invented Here (NIH) to Proudly Found Elsewhere (PFE). Those who can make this transition will have a key advantage in the marketplace.

In order to properly leverage the open innovation model, you need to think very carefully about the treatment of intellectual property. In the closed model, companies historically accumulated IP to provide design freedom to their internal staff and to avoid costly litigation. As a result, most patents are actually worth very little to these companies, and there is growing evidence (see below) that the vast majority of patents are never used by the business that holds them.

By embracing an open-innovation corporate culture, IP represents a new class of assets that can deliver additional revenues to the current business model. IP can also lead to new businesses and new business models. Open innovation implies that companies should be both active sellers of IP (when it does not fit their own business model) and active buyers of IP (whenever external IP does fit their own product roadmap).

Consider your own organization and evaluate its patent utilization rate. Think of all the patents that your company owns. Then ask yourself what percentage of these patents is actually used in at least one of your businesses.

Often people don’t even know the answer because no one has ever asked the question. In cases where companies have taken the trouble to find out, the percentage is often quite low, between 10 and 30%.

This means that 70-90% of a company’s patents are not used. In most companies, these unused patents are not offered outside for licensing either. Inside-out open innovation is an obvious opportunity for additional growth and profits.

Although comprehensive studies of patent utilization rates are not yet available, a 2001 Northwestern University Law Review article by Mark Lemley cited studies that report a large fraction of patents are neither used nor licensed by firms.

Julie L. Davis and Suzanne Harrison reported in their 2001 book, Edison in the Boardroom: How Leading Companies Realize Value from Their Intellectual Assets, that more than half of Dow’s patents were unutilized.

And Nabil Sakkab reported in 2002 that less than 10% of Procter & Gamble’s patents were utilized by one of P&G’s businesses.

In 2006, Sakkab reported that P&G, after moving to an open-innovation model, was able to achieve “sustained and steady top-line growth,” with 35% of its new products having elements that originated outside the company.

Some may consider open innovation a rationale for outsourcing all R&D. Does this mean I can save costs by firing my R&D team?

The answer is no, as this misrepresents the nature of open innovation.

Often mature companies without large, internal R&D programs rely heavily on acquisitions, strategic alliances, or universities and tap into the innovations of others. But to really transfer knowledge effectively, you need a certain amount of creative abrasion and a certain amount of dwell time and “impedance matching” working together on it.

Companies must still perform the difficult and arduous work necessary to convert promising research results into products and services that satisfy customers’ needs. Open innovation works best when you have R&D employees who can collaborate with partners from inside and outside the four walls of your company.

Innovative companies have also begun to create positions called “technology scouts” or “innovation scouts,” often making that role part of a senior level technical executive job description. That person actively searches for new technologies and ideas outside the firm. However, you need to be able to harness that technology once you find it. Designing and managing these types of innovation communities is going to become increasingly important to open innovation’s future.

It is the logic of open innovation that the most successful innovators integrate all their ideas, expertise, and skills and deliver the results to the marketplace, using the most effective and efficient means possible. Whether using ideas from inside or outside the organization, those practicing open innovation will create new value and accelerate their time to market.

–Henry Chesbrough, credited with the theory and coinage of the term “open innovation,” is executive director of the Program for Open Innovation at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is also an adjunct professor. He is the author of several books, including Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, and he serves on the business advisory board for Open Photonics Inc. His PhD in business administration and public policy is from the Haas School and his MBA from Stanford.

–SPIE Senior Member Jason M. Eichenholz is CEO of Open Photonics Inc. and an active evangelist and practitioner of open innovation. He has served as a senior technology leader and executive at several leading photonics companies including Halma, Ocean Optics, and Newport/Spectra-Physics. He has a PhD in optical sciences and engineering from the University of Central Florida where he is also a courtesy faculty member.

SPIE corporate member Open Photonics Inc. (OPI) was formed specifically to accelerate the commercialization of photonics technologies by linking the best minds in the industry with existing infrastructure and market channels.

Its Photonic Horizons™ competitive grant program is a crowd-sourcing and open-innovation framework that fosters collaboration between established companies and the researchers and inventors who have ideas with commercial potential.

Winners of the annual program are chosen and funded by OPI clients with peer review by OPI technical and business advisory boards. Initial-phase grants of $10,000 are for a six-month, proof-of-concept project. Second-stage grants, up to $100,000, are for a six- to 12-month prototype development project.

OPI team and advisory board members manage the entire grant process from concept validation through eventual prototype development completion.

SPIE Professional covered innovation scouting and open innovation in a 2010 article about a survey conducted by Nerac.

Because innovation scouting is a key element of open innovation, Nerac conducted a 2009 survey to benchmark the practices of innovation and technology scouts.

The survey found that companies in the optics, imaging, and lasers industries reported some of the highest usage of innovation scouts, with 45% of respondents from these industries indicating they have scouting programs.

Furthermore, 100% of those optics and photonics companies reported that their innovation scouting efforts were very successful or moderately successful.

The survey also found a high percentage of employees in scouting roles at optics and photonics companies, compared to employees in other companies. Some 44% of the optics and photonics respondents had more than 25 innovation scout employees, compared to 40% of all respondents who had fewer than three innovation scouts.

- Read more about the Nerac survey on innovation scouting.

- Have a question or comment about this article? Write to us at spieprofessional@spie.org.

- To receive a print copy of SPIE Professional, the SPIE member magazine, become an SPIE member.