Chemical detection from above

When soldiers move into a new area they want to check that there are no harmful substances there. Taking an instrument into the area is not really an option though; if there were any warfare or nerve agents then the instrument operator would be affected by them in the process of analyzing the area.

Telops (St-Jean-Baptiste, Québec) offers a tool to analyze an area remotely -- from a distance of 5km away. And the company has now taken this idea a stage further. Later this year it will begin shipping instruments that can operate from aircraft.

Image of a scene in a spectral slice at 10 microns calibrated in brightness temperature.

The potential applications of this go beyond military site investigations. Philipps Laquex, business development manager of Telops, pointed out that this approach is a great way to check for leaks from a gas pipeline. He added that, increasingly, the company is receiving requests from environmental research groups too.

Telops' hyperspectral imaging spectrometer, known as FIRST, is based on a Michelson interferometer and an infrared camera. Fourier Transforms are performed to get one spectrum for each pixel of the camera to give high spatial resolution. "We try to extract signatures that aren't typical," commented Laquex.

The FIRST instrument is already on the market and is used by the military and the chemical industry, which might, for example, locate the instrument near a factory in order to monitor for leaks. The technique does not just reveal what compounds there are but also their concentration. "For agents like SF-6, one of the most popular warfare agents, we've been able to detect levels of less than 10 ppm at distances of more than 1km away," said Laquex.

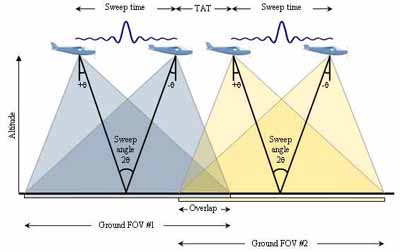

Making this instrument airborne is not a straightforward process, however. The first problem is that the equipment is sensitive to vibrations and movements, which there are far more of in an aircraft than in a stationary location on the ground. Telops is customizing commercial stabilization platforms to use with its instrument. In addition, the company is controlling the way that the instrument is operated in the air.

The aircraft's movement causes another problem: it means that the sensor is moving so the camera scene changes all the time. The instrument has to compensate for this as well. "We need to take reference measurement and calibrate the instrument with background subtraction," said Laquex.

Image motion compensation mirror cancels the smear effect during a datacube acquisition by correcting the staring angle of the FIRST.

There are other more long-term challenges as well. Currently, the processing is not performed in real time as the measurement is being made. The next step, according to Laquex, is to incorporate onboard intelligence so that the spectra can be produced immediately after the measurements are made.

Another challenge is the sheer amount of data generated. A full frame can be 500 Mb. However, Laquex pointed out that many chemical agents have very distinctive signatures in their spectra. "In order to detect most chemical warfare agents you don't need a very high spectral resolution. High resolution generates too much data and slows things down. You just need the resolution that is necessary to detect the compounds," he said.

The airborne instrument was described at the SPIE Europe Security + Defence meeting in Cardiff, UK, in September 2008. Siân Harris is a UK-based freelance writer.